Gospel Notes by Michael Whelan SM

“If another member of the church sins against you, go and point out the fault when the two of you are alone. If the member listens to you, you have regained that one. But if you are not listened to, take one or two others along with you, so that every word may be confirmed by the evidence of two or three witnesses. If the member refuses to listen to them, tell it to the church; and if the offender refuses to listen even to the church, let such a one be to you as a Gentile and a tax collector. Truly I tell you, whatever you bind on earth will be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth will be loosed in heaven. Again, truly I tell you, if two of you agree on earth about anything you ask, it will be done for you by my Father in heaven. For where two or three are gathered in my name, I am there among them” (Matthew 18:15-20 – NRSV).

Introductory notes

General

There is a similar text in Luke: “Be on your guard! If another disciple sins, you must rebuke the offender, and if there is repentance, you must forgive. And if the same person sins against you seven times a day, and turns back to you seven times and says, ‘I repent,’ you must forgive” (17:3-4).

See also something similar in John: “Those whose sins you forgive etc” (20:23).

Reconciliation is a crucial part of human existence. It becomes a very concrete and immediate issue in community life. Matthew’s audience would also have been aware of the instruction of the Torah: “You shall not hate in your heart anyone of your kin; you shall reprove your neighbor, or you will incur guilt yourself. You shall not take vengeance or bear a grudge against any of your people, but you shall love your neighbor as yourself: I am the Lord” (Leviticus 19:17-18). And, as to the process, there are some laws that apply. For example: “A single witness shall not suffice to convict a person of any crime or wrongdoing in connection with any offense that may be committed. Only on the evidence of two or three witnesses shall a charge be sustained” (Deuteronomy 19:15).

Specific

member of the church: This phrase is used by the NRSV to render the Greek word adelphos which literally means “brother”.

against you: “This phrase is absent from many important manuscripts. It was probably a scribal addition under the influence of Matt 18:21. Thus in the original Matthean text the offense was unspecified but most likely had implications for the entire community as the three-step process implies” (Daniel J Harrington, The Gospel of Matthew, Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2007, 268).

point out: The Greek verb is elegxon and it is generally translated as “expose”, “reprove” or “convict”. The Jerusalem Bible translates it as “have it out with him”. The whole thrust of this interaction seems to be towards an honest and transparent interaction: “We are in this together, and we need to sort it out together”. Refer again to the Leviticus text cited above: “You shall not hate in your heart anyone of your kin; you shall reprove (the Greek verb elegxon is used in the Septuagint) your neighbor, or you will incur guilt yourself . . .”

take one or two others along with you: If the first step fails, then move to the second step. This seems to be based on Deuteronomy 19:15 cited above.

tell it to the church: “Although Gk. ekklēsía became a distinctively Christian word, it has both a Greek and an OT history. In the Greek world it was used of a public assembly summoned by a herald (< ek, “out,” and kaleín, “to call”; cf. Acts 19:32, 39f). In the LXX it was used for the Heb. qāhāl, which denotes the congregation or people of Israel, especially as gathered before the Lord (cf. Acts 7:38). It is of interest that behind the NT term stand both Greek democracy and Hebrew theocracy, the two being brought together in a theocratic democracy or democratic theocracy.

“In the teaching of Jesus Himself there is little mention of the Church. The only two references in the Gospels are both in Matthew (16:18: “On this rock I will build my church,” and 18:17: “Tell it to the church”). In the second of these the reference might be to the Jewish synagogue, though the general context of Mt. 18 seems to suggest the emergent Christian community. Apart from the critical questions raised by some scholars, these verses give rise to many problems. For example, do they denote the intention of Jesus to found a Church? If so, or even if He only foresees its creation, what is the relation of this Church to the older congregation of the Lord? Is the new to continue the old, to supersede it, or to be quite different and perhaps parallel? Again, what is the relationship between the Church and the kingdom of God or of heaven which is the main theme of the teaching of Jesus? Are the two completely different? Are they synonymous? Or is the Church as the present sphere of Christ’s rule a provisional or partial form of the kingdom?

“These questions are easier to ask than to answer, and it is probably in terms of a qualified comprehensiveness that true solutions are to be sought. Thus, the Church of Jesus is a new body, yet there is a continuity of fulfillment in relation to the OT congregation. Again, the kingdom is quite evidently not the Church, for we could hardly proclaim the Church as the first apostles proclaimed the kingdom (Acts 8:12). On the other hand, we certainly cannot say that the Church is an alternative after the rejection of the kingdom. To the extent that the Church is a fellowship of those who have accepted the kingdom, submitted to its rule, and become its heirs, we may rather believe that it is a creation and instrument and therefore a form and manifestation of the kingdom prior to its final establishment in glory” (G W Bromiley, “Church” in G. W. Bromiley (Ed.), The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, Revised (Vol. 1), Wm. B. Eerdmans, 1979–1988, 693).

It is interesting to note that “the Qumran community had a similar threefold procedure: ‘let him rebuke him on the very same day lest he incur guilt because of him. And furthermore, let no man accuse his companion before the Congregation without having first admonished him in the presence of witnesses” (Leon Morris, The Gospel according to Matthew, Grand Rapids, MI; Leicester, England: W.B. Eerdmans; Inter-Varsity Press, 1992, 468).

let such a one be to you as a Gentile and a tax collector: This suggests that the ekklesia had to face some difficult decisions in a very tough environment. Daniel Harrington writes: “The expression presupposes a largely Jewish-Christian milieu (see Matt 5:46–47; 6:7) in which such people are looked down upon. Nevertheless, earlier in the Gospel such persons have shown great faith in Jesus (8:1–11; 9:9–13; 11:19; 15:21–28). The sentence sounds like a decree of excommunication. For shunning erring Christians, see 1 Cor 5:1–5; 2 Thess 3:6–15; 2 John 10” (Daniel Harrington, op cit, 269). It is worth noting the phrase, “be to you”. It is not “be to the church”.

whatever you bind …. loose: “The power to bind and loose, previously bestowed on Peter in 16:19, is now given to all the disciples at large. Taken in context with 18:15–17, that power would seem to concern either the imposing (and lifting) of decrees of excommunication or the forgiving (and not forgiving) of sins” (Daniel J Harrington, op cit, 269).

Healing the wounded community

In today’s Gospel – Matthew 18:15-20 – we are told of Jesus’ instructions on how to deal with “sin” in the community. In interpreting those instructions as reported for us by Matthew, we need to recognize that a crucial distinguishing mark of our life and times is a certain individualism. We more readily think and speak in the first-person singular. Thus, my rights, my needs, my wishes, tend to take precedence over the common good.

Indeed, it must be acknowledged that this individualism has also crept into the Church and influenced our understanding of the Christian life. Consider two examples. Firstly, Eucharist is primarily a communal event. Yet, our celebration of the Eucharist had become, by the middle of the 20th century, more a private devotion than a communal celebration. Secondly, all sin is, in some way, a violation of our unity in Christ. Yet, it is commonly viewed as simply a private affair, between me and God. Is there such a thing as private sin? We need to recover the deep sense of the common good that is an essential part of life in Christ.

In Jesus’ time, “we” and “us” are the primary lenses through which the world is interpreted. Living and dying – and wrongdoing – are always communal events. More particularly, the “we” and “us” of Matthew’s audience are defined by the Covenant. The people derive their very identity from God’s loving choice. They are not constituted as a group primarily through culture or ethnicity or law or any other human motivation. They exist as a community primarily because God brought them together. They – we – are, therefore, a pilgrim people, a people not only gathered by God’s loving initiative but going where God leads. Jesus is the heart and soul of this community of pilgrims. Through him, with him and in him, we become what we are.

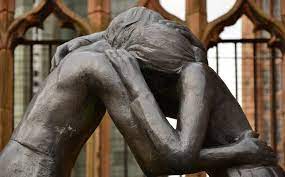

It is in this context that Matthew speaks of “sin”. “Sin”, as spoken of here, is not a private affair. The community has been wounded. What happens to the individual member, happens to the group. A healing response is needed. It is significant, therefore, that the individual is not expected to take the healing initiative. The community – through its representatives – takes the initiative to heal the wound created by the adverse behaviour of the individual. The community, in fact, is expected to go to extraordinary lengths to seek that healing.

There is a special sensitivity to be employed in this process: “go and point out the fault when the two of you are alone”. Care for the common good is sought. Beware though! Under the influence of individualism, “pointing out the fault” can mask an insidious sin. T S Eliot sounds a warning when he places wise words on the lips of Thomas à Becket: “For those who serve the greater cause may make the/ cause serve them,/ Still doing right” (T S Eliot, Murder in the Cathedral, A Harvest Book, 1935, 45).