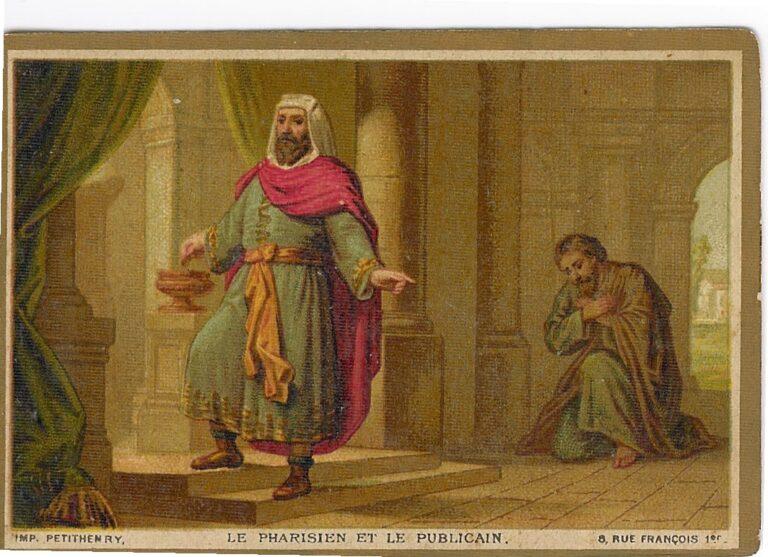

Jesus also told this parable to some who trusted in themselves that they were righteous and regarded others with contempt: “Two men went up to the temple to pray, one a Pharisee and the other a tax collector. The Pharisee, standing by himself, was praying thus, ‘God, I thank you that I am not like other people: thieves, rogues, adulterers, or even like this tax collector. I fast twice a week; I give a tenth of all my income.’ But the tax collector, standing far off, would not even look up to heaven, but was beating his breast and saying, ‘God, be merciful to me, a sinner!’ I tell you, this man went down to his home justified rather than the other; for all who exalt themselves will be humbled, but all who humble themselves will be exalted” (Luke 18:9-14 – NRSV)

Introductory note

General

Like the parable we have just read in Luke 18:1-8 “about the need to pray continually and never lose heart” – and addressed to the disciples – this parable of the two men who went up to the temple to pray – addressed directly to the Pharisees – is about much more than prayer. The parable is fundamentally an assertion of God’s sovereignty and a rebuttal of behaviours that would usurp that sovereignty. God’s sovereignty is expressed primarily in mercy. The parable, in bringing this teaching into focus, is also a very pointed affront to the Pharisees who teach something quite different – not the first such affront in Luke and not the last either. There is a polemic here.

This parable is unique to Luke, though we find a similar sentiment in Matthew’s Sermon on the Mount – see 6:1-6.

“The parable itself is one that invites internalization by every reader because it speaks to something deep within the heart of every human. The love of God can so easily turn into an idolatrous self-love; the gift can so quickly be seized as a possession; what comes from another can so blithely be turned into self-accomplishment. Prayer can be transformed into boasting. Piety is not an unambiguous posture. The literary skill revealed by the story matches its spiritual insight. The pious one is all convoluted comparison and contrast; he can receive no gift because he cannot stop counting his possessions. His prayer is one of peripheral vision. Worse, he assumes God’s role of judge: not only does he enumerate his own claims to being just, but he reminds God of the deficiency of the tax-agent, in case God had not noticed.

“In contrast, the tax-agent is utter simplicity and truth. Indeed, he is a sinner. Indeed, he requires God’s gift of righteousness because he has none of his own. And because he both needs and recognizes his need for the gift he receives it.

“The parables together do more than remind us that prayer is a theme in Luke-Acts; they show us why prayer is a theme. For Luke, prayer is faith in action. Prayer is not an optional exercise in piety, carried out to demonstrate one’s relationship with God. It is that relationship with God. The way one prays therefore reveals that relationship. If the disciples do not ‘cry out day and night’ to the Lord, then they in fact do not have faith, for that is what faith does. Similarly, if prayer is self-assertion before God, then it cannot be answered by God’s gift of righteousness; possession and gift cancel each other” (Luke Timothy Johnson, The Gospel of Luke, Collegeville, MN: The Liturgical Press, 1991, 274).

Specific

Pharisee …. tax collector: The “tax collectors (and sinners)” in Luke’s Gospel have been consistently presented as people open to Jesus and his message – see 3:12; 5:27, 29 &30; 7:34; 15:1 – while the “Pharisees (with lawyers and scribes)” have been consistently presented as being closed to Jesus and his message – see 10:19; 16:15; also 5:21, 30, 33; 6:2, 7; 7:39; 11:38–39, 42, 43, 53; 12:1; 13:31; 14:1–3; 15:1–2; 16:14; 17:20.

like this tax collector: The Pharisee in the parable is reflecting the contempt that the Pharisees in general had for the tax collectors. We heard this before in Luke – see 5:30; 7:34; 15:1. The listener is forced to wonder about the focus of the Pharisee’s mind and heart.

God, be merciful to me, a sinner: “Four aspects of the tax-agent’s humility are briefly indicated by Luke: 1) he stood far off; 2) he kept his eyes lowered; 3) he beat his breast (as a sign of repentance, cf. Luke 23:48); 4) he cries out for mercy (cf. 17:13). Luke makes the tax-agent different from the Pharisee in two obvious respects. Rather than suggest that he is dikaios (“righteous”), much less give evidence for it, he declares himself to be exactly what the Pharisee considered him a sinner (harmartōlos). Furthermore, rather than speak to God with reference to the Pharisee (with peripheral vision), he straightforwardly begs for mercy” (Luke Timothy Johnson, op cit, 272).

Reflection

In 1897 H G Wells published his haunting novel, The Invisible Man. It is the story of a former medical student – Griffin – who has discovered chemicals that can make matter invisible. He uses the chemicals on himself. He becomes invisible. He wraps himself in bandages in order to be seen. So begins a descent into a horrible abyss. The final resolution, as it were, comes with his death. It is a horror story. Interestingly enough, there have been a number of movies – beginning in 1933 – and a TV series, based on this horror story. In fact, there is another invisible man movie to be released in the coming year. It seems that H G Wells brought to light a deep and universal human theme. But he was not the first to explore this theme. We find it in the Bible, in the story of Adam and Eve. They tried to make themselves invisible by putting on fig leaves. There is something awfully pathetic about us human beings, the way we “bandage” ourselves in order to be seen, when the bandages are removed, we are invisible. Seeming has replaced being.

Today’s Gospel – Luke 18:9-14 – draws a contrast between two people. The first is a heavily “bandaged” individual, a man who uses his presumed righteousness as fig leaves – ‘God, I thank you that I am not like other people: thieves, rogues, adulterers, or even like this tax collector. I fast twice a week; I give a tenth of all my income.’ It would indeed be very pertinent to ask such an individual: “Is it yourself?” The second man, by way of contrast, is making no attempt to hide, he is what he is: ‘God, be merciful to me, a sinner!’ It would be entirely impertinent to ask this man that same question. It is himself!

The American poet, playwright, artist and essayist, E.E. Cummings, had something to say about this matter:

“To be nobody but yourself in a world/ which is doing its best night and day,/ to make you everybody else; means to fight/ the hardest battle which any human being/ can fight and never stops fighting.”

What the Pharisee said about himself may have been quite true. Jesus’ point is that God does not want our performances – even if they are moral. God wants us. The true self is made in the image and likeness of the Self-emptying God, incarnate in Jesus of Nazareth. I become my true self, not through my virtues but through God’s grace. My task – and this takes constant work – is to get out of the way, to bring my emptiness and neediness to God. In his journal, E.E. Cummings writes a brief prayer: “may I be I is the only prayer–not may I be great or good or beautiful or wise or strong” (Richard S. Kennedy, E.E. Cummings Revisited, Twayne Publications, 1993).

Is it a pertinent question to ask of you, as you turn up for a new day: “Is it yourself?”