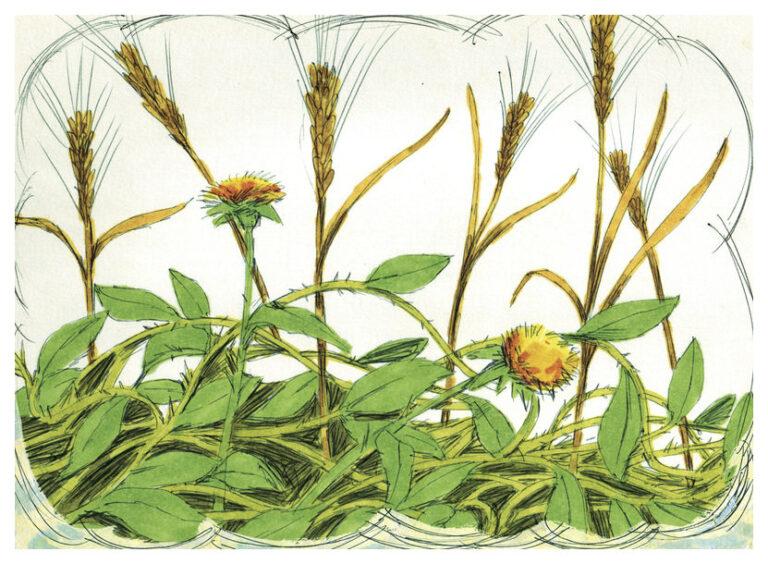

He put before them another parable: “The kingdom of heaven may be compared to someone who sowed good seed in his field; but while everybody was asleep, an enemy came and sowed weeds among the wheat, and then went away. So when the plants came up and bore grain, then the weeds appeared as well. And the slaves of the householder came and said to him, ‘Master, did you not sow good seed in your field? Where, then, did these weeds come from?’ He answered, ‘An enemy has done this.’ The slaves said to him, ‘Then do you want us to go and gather them?’ But he replied, ‘No; for in gathering the weeds you would uproot the wheat along with them. Let both of them grow together until the harvest; and at harvest time I will tell the reapers, Collect the weeds first and bind them in bundles to be burned, but gather the wheat into my barn.’” (Matthew 13:24-30 – NRSV)

The following may also be read:

He put before them another parable: “The kingdom of heaven is like a mustard seed that someone took and sowed in his field; it is the smallest of all the seeds, but when it has grown it is the greatest of shrubs and becomes a tree, so that the birds of the air come and make nests in its branches.”

He told them another parable: “The kingdom of heaven is like yeast that a woman took and mixed in with three measures of flour until all of it was leavened.”

Jesus told the crowds all these things in parables; without a parable he told them nothing. This was to fulfill what had been spoken through the prophet: “I will open my mouth to speak in parables; I will proclaim what has been hidden from the foundation of the world.”

Then he left the crowds and went into the house. And his disciples approached him, saying, “Explain to us the parable of the weeds of the field.” He answered, “The one who sows the good seed is the Son of Man; the field is the world, and the good seed are the children of the kingdom; the weeds are the children of the evil one, and the enemy who sowed them is the devil; the harvest is the end of the age, and the reapers are angels. Just as the weeds are collected and burned up with fire, so will it be at the end of the age. The Son of Man will send his angels, and they will collect out of his kingdom all causes of sin and all evildoers, and they will throw them into the furnace of fire, where there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth. Then the righteous will shine like the sun in the kingdom of their Father. Let anyone with ears listen!” (Matthew 13:31-43 – NRSV)

Introductory notes

General

This parable of the darnel – or tares in the wheat – is unique to Matthew.

Once again, Matthew addresses a troubling experience of his audience: They have accepted Jesus, why do the majority of the Jews not accept him? What are they to make of this division? Daniel Harrington writes: “The parable of the wheat and weeds (13:24–30) follows upon the parable of the sower. The setting is agricultural, and the subject is the mixed reception accorded Jesus’ word of the kingdom. The problem faced in the parable is the fact that some Jews accept and others reject the gospel. The issue before the Christians is, How do we react to this reality? The parable, which surely has allegorical features (though not as many as Matt 13:36–43 supplies), counsels patience and tolerance in the present. The assumption behind this counsel is the confidence that at the final judgment there will be a separation between the just and the unjust along with appropriate rewards and punishments.” (Daniel J Harrington, The Gospel of Matthew, Liturgical Press, 2007, 208.)

Specific

The kingdom of heaven: The expression typical of Matthew, is just another way of speaking of “the kingdom”, the centerpiece of Jesus’ preaching: “According to all three Synoptics, the kingdom of God was the central theme of the preaching and teaching of Jesus. The phrase occurs fourteen times in Mark, thirty-two times in Luke, but only four times in Matthew (12:28; 19:24; 21:31, 43). In its place, Matthew substitutes ‘the kingdom of heaven’ (lit ‘the kingdom of the heavens’, Gk. hē basileía tōn ouranōn). Although dispensational theology has customarily made a theological distinction between these two terms, the simple fact is that they are quite interchangeable (cf. Mt. 19:23 with v 24; Mk. 10:23). In Jewish rabbinic literature, the common phrase is ‘the kingdom of the heavens’ (Dalman, pp. 91ff). In Jewish idiom, ‘heaven’ or some similar term was often used in place of the holy name (see Lk. 15:18; Mk. 14:61).” (G E Ladd, “Kingdom Of God” in G. W. Bromiley (Ed.), The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, Revised (Vol. 3) Wm. B. Eerdman, 1979-1988, 24.)

someone who sowed good seed: The audience is called to listen to the whole process – the sowing and growing. And so we must ask: What is happening here?

while everybody was asleep: This suggests two contrasting interpretations. Firstly, nobody notices the bad thing that is happening in their own backyard. Secondly, the growth continues peaceably until the end. The first interpretation suggests something about being in the kingdom at his moment, while the second suggests something about the end time. This deepens the question, “What is happening here?” You cannot answer this question – you cannot judge – with any confidence until all is revealed at the close of the ages and the fullness of the kingdom.

Let both of them grow together: The idealist will rush to get rid of the weeds and the work of the “enemy” for it is spoiling the crop! In doing this, the idealist will probably also uproot the wheat as well. The realist waits until the end, when the weeds and the wheat can both be removed. The weeds can then be separated out and thrown away. The wheat can be harvested. The “enemy” is thus defeated at the end.

Reflection

Oscar Wilde once famously said that there is only one thing worse than not having your expectations met, that is having them met. As with most of the witty sayings of Wilde, there is much more to this than meets the eye. Disappointment – implied in Wilde’s comment – is quite simply part of human existence. St Augustine implies it in the opening paragraph to his Confessions: “Our hearts are restless until they rest in You”. At a more mundane level of human experience, we are all familiar with disappointment. Sometimes it comes to us because our expectations are unreal or because we – or someone else – have behaved irresponsibly or because of a recurring bad habit or compulsion or it just comes for no apparent reason. Coming to terms with disappointment is one of life’s central challenges. If we do that well we are likely to live well. If we do that badly we are likely to live badly.

Today’s parable – the tares and the wheat (Matthew 13:24-30) – may be understood as a metaphor for coming to terms with disappointment, especially disappointment with ourselves. Disappointment often marks growth moments as we journey beyond the self-centred life towards the Mystery-centred life. This will include many movements from wilful attempts to control life towards a gracious submission to what cannot be controlled. Slowly but surely, the expectation of conquest can be displaced by an appreciation of life as gift. In our honest attempts to be faithful disciples of Jesus, we can be lured – unwittingly – into trying to pull out the weeds in our lives. If the truth be told, we would feel much more in control if we got rid of the weeds.

Adrian van Kaam writes well of this movement: “The Lord will never ask how successful we were in overcoming a particular vice, sin, or imperfection. He will ask us, ‘Did you humbly and patiently accept this mystery of iniquity in your life? How did you deal with it? Did you learn from it to be patient and humble? Did it teach you to trust not your own ability but My love? Did it enable you to understand better the mystery of iniquity in the lives of others? Did it give you the most typical characteristic of truly religious people – that they never judge or condemn the sin and imperfection of others?

“Genuinely religious people know from their own lives that the demon of evil can be stronger than any human being even in spite of their best attempts; they know that it is the patience, humility, and charity learned from this experience that count. Success and failure are accidental. The joy of the Christian is never based on their personal religious success but on the knowledge that their Redeemer lives. The genuine Christians are those who are constantly aware of their need of salvation. Acceptance of the mystery of iniquity in our project of existence is a school of mildness, mercy, forgiveness, and loving understanding of our neighbor” (Adrian van Kaam, Religion and Personality (Revised Edition), Dimension Books, 1980, 14-15).