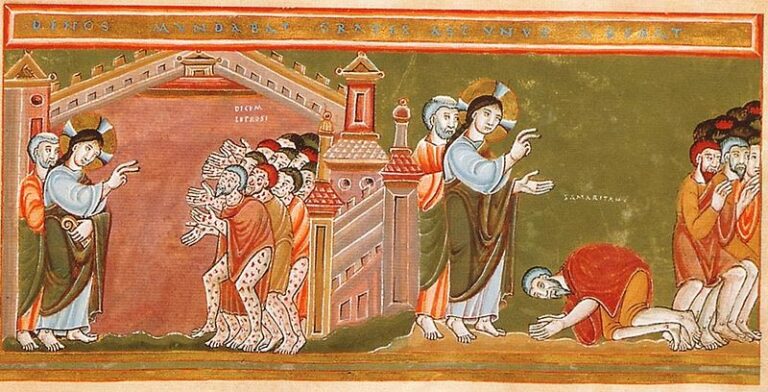

On the way to Jerusalem Jesus was going through the region between Samaria and Galilee. As he entered a village, ten lepers approached him. Keeping their distance, they called out, saying, “Jesus, Master, have mercy on us!” When he saw them, he said to them, “Go and show yourselves to the priests.” And as they went, they were made clean. Then one of them, when he saw that he was healed, turned back, praising God with a loud voice. He prostrated himself at Jesus’ feet and thanked him. And he was a Samaritan. Then Jesus asked, “Were not ten made clean? But the other nine, where are they? Was none of them found to return and give praise to God except this foreigner?” Then he said to him, “Get up and go on your way; your faith has made you well” (Luke 17:11-19 – NRSV)

Introductory notes

General

Most of Jesus’ ministry occurred within the boundaries of Israel and most of his audience were Jews. In this text we hear of one of those few occasions Jesus and his disciples went into Gentile territory: “On the way to Jerusalem Jesus was going through the region between Samaria and Galilee.”

This is no ordinary miracle event. There is a profound irony here. First of all, Jesus shows himself to be the one who respects “the law and the prophets” – much more so than the religious authorities who claim to be the teachers and protectors of that tradition but actually do not live out the Covenant. Secondly, the one who recognizes the presence of the Kingdom, is a Samaritan. The situation is well described earlier: “The Pharisees, who were lovers of money, heard all this, and they ridiculed him. So he said to them, “You are those who justify yourselves in the sight of others; but God knows your hearts; for what is prized by human beings is an abomination in the sight of God. ‘The law and the prophets were in effect until John came; since then the good news of the kingdom of God is proclaimed, and everyone tries to enter it by force. But it is easier for heaven and earth to pass away, than for one stroke of a letter in the law to be dropped’” (16:14-17).

Specific

on the way to Jerusalem: Luke has more than thirty explicit references to Jerusalem in his Gospel. As a baby, “according to the law of Moses, (his parents) brought him up to Jerusalem to present him to the Lord” (2:22); “Now every year his parents went to Jerusalem for the festival of the Passover. And when he was twelve years old, they went up as usual for the festival. When the festival was ended and they started to return, the boy Jesus stayed behind in Jerusalem” (2:41-43); during the tempting in the desert, “Then the devil took him to Jerusalem” (4:9); at the transfiguration Moses and Elijah “appeared in glory and were speaking of his departure (exodon), which he was about to accomplish at Jerusalem” (9:31); then the journey to Jerusalem begins in earnest: “When the days drew near for him to be taken up, he set his face to go to Jerusalem” (9:51); “Jesus went through one town and village after another, teaching as he made his way to Jerusalem” (13:22); “it is impossible for a prophet to be killed outside of Jerusalem” (13:33); in today’s text, Jesus is “on the way to Jerusalem” when he encounters the ten lepers (17:11); he warns the disciples, as they continue the journey to Jerusalem, “we are going up to Jerusalem, and everything that is written about the Son of Man by the prophets will be accomplished” (18:31); “he went on to tell a parable, because he was near Jerusalem, and because they supposed that the kingdom of God was to appear immediately” (19:11); after he has told the parable, “he went on ahead, going up to Jerusalem” (19:28); finally: “repentance and forgiveness of sins is to be proclaimed in his name to all nations, beginning from Jerusalem. You are witnesses of these things. And see, I am sending upon you what my Father promised; so stay here in the city until you have been clothed with power from on high (24:47-49)”. One commentator writes of the significance of Jerusalem:

“Ever since the ‘stronghold of Zion’ was seized by David (2 Sam 5:7; 1 Chron 11:5), Jewish attention has been focused upon one city, Jerusalem. Shortly after its capture Jerusalem became the political, economic, military, social and religious center for ancient Israel. The successful concentration of both earthly and heavenly power in Jerusalem insured that this city was destined to dominate Jewish geographical imagination forevermore. Not only was Jerusalem thought to be the ‘center’, or ‘navel’, of the whole earth (Ezek 5:5; 38:12; 1 Enoch 26:1; Jub. 8:11, 19) but also ideal figurations of this holy city, this Zion, became stock symbols for Jewish worship and eschatology. Jewish dreams of what ought to be and what would be were uniquely tied to this specific plot of land (Gowan). Jerusalem, or Zion, thus replaced Sinai as the mountain of Yahweh’s presence (Levenson).

“Given Jerusalem’s importance for Jewish communal identity (Kee, 18–22), it is curious that imagery about Zion does not play a larger role within early Christian reflection. ‘Zion’ (Sion) occurs only four times in the later writings of the NT and the apostolic fathers (Heb 12:22; 1 Pet 2:6; Rev 14:1; Barn. 6.2), while the phrase ‘holy city’ (hagia polis) appears only four times in the later writings of the NT (Rev 11:2, 21:2, 10; 22:19) and never in the apostolic fathers. References to ‘Jerusalem’ (Ierosolyma; Ierousalem), although more plentiful, are concentrated: fifty-nine occurrences in Acts; only five elsewhere (Heb 12:22; Rev 3:12; 21:2, 10; 1 Clem. 41.2). Part of the explanation may be that Roman occupation and the destruction of Jerusalem held in check wholesale Christian appropriation of the tradition (see Barn. 16.4–5; Robinson). Further, Jesus, as the embodiment of God’s presence, reshaped Jewish eschatology. Since Christian hope was uniquely tied to a person and not to a place, the Zion tradition was reformatted in its application to Jesus (1 Pet 2:6; Barn. 6.2; cf. Is 28:16). Finally, many of the royal themes associated with Zion were carried along without specific reference to the city; for example, language about kingdom, temple, covenant and priesthood. The few places in which Christianity did explicitly use the Zion tradition in a substantive way thus merit close attention” (C C Newman, “Jerusalem, Zion, Holy City”, in R. P. Martin & P. H. Davids (Eds.), Dictionary of the later New Testament and its developments, Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1997, 561).

Jesus, Master, have mercy on us: This cry of the lepers is similar to the cry of the blind beggar – Bartimaeus – in Mark 10:46: “Jesus, Son of David, have mercy on me!” This is basis for the Jesus Prayer – “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me a sinner”.

Reflection

In the thinking of Jesus’ day, “knowledge of a name gave power over the thing named; to know a god’s name was to be able to call on him and be certain of a hearing” (Footnote to Exodus 3:14 in The Jerusalem Bible). This background is helpful in interpreting the Commandment, “You shall not utter the name of Yahweh etc.” God’s sovereignty is sacrosanct! Interestingly enough, on 29 June 2008, the Roman Congregation for Divine Worship and Discipline of the Sacraments, issued a directive that the use of ‘Yahweh’ in the Roman Catholic liturgy should be dropped in faithfulness to the Jewish tradition and the practice of the early Church.

A name and its use implies a certain relationship. The utter transcendence and otherness of God must be maintained. But with the Incarnation – and the introduction to the world of the name, ‘Jesus of Nazareth’, there came a profound and lasting emphasis on the utter immanence and nearness of God to be held in tension with the utter transcendence and otherness. In his conversion experience Paul is told: “I am Jesus, whom you are persecuting” (Acts 9:5). This clearly had an immense impact on Paul’s thinking. But it seems there had already been a change in the way the early Christians thought of and named God. Ananias, in a vision with ‘the Lord’ is told that Paul will “suffer for the name” (9:14). And when the first group of Christians heard Paul, they exclaimed in wonder: “Is not this the man who made havoc in Jerusalem among those who invoked this name” (Acts 9:21). Paul links Jesus of Nazareth with the One revealed in Exodus 3:1-15: “Therefore God also highly exalted him and gave him the name that is above every name, so that at the name of Jesus every knee should bend, in heaven and on earth and under the earth, and every tongue should confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father” (Philippians 2:9-11).

In today’s Gospel – Luke 17:11-19 – the lepers call on Jesus by name: “Jesus, Master, have mercy on us!” It is speech of intimacy – and Jesus accepted it. Similarly, the blind beggar – Bartimaeus – cries out in Mark 10:46: “Jesus, Son of David, have mercy on me!” This is the basis for the “Jesus Prayer” that has been prayed by thousands of Christians down the centuries: “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me a sinner”.

There is a delightful story told of Pope John XXIII. On 7 March 1963, he received Nikita Khrushchev’s daughter, Rada, and her husband Alexis Adzhubei at the Vatican. The Pope spoke to Rada in French: “Madame, I know that you have three children, and I know their names. But I would like you to tell me their names, because when a mother speaks the names of her children, something very special happens” (Peter Hebblethwaite, John XXIII: Pope of the Council, Harper Collins, 1994, 482). What’s in a name? A lot – when it is spoken with love.