At that time Jesus said, “I thank you, Father, Lord of heaven and earth, because you have hidden these things from the wise and the intelligent and have revealed them to infants; yes, Father, for such was your gracious will. All things have been handed over to me by my Father; and no one knows the Son except the Father, and no one knows the Father except the Son and anyone to whom the Son chooses to reveal him.

“Come to me, all you that are weary and are carrying heavy burdens, and I will give you rest. Take my yoke upon you, and learn from me; for I am gentle and humble in heart, and you will find rest for your souls. For my yoke is easy, and my burden is light” (Matthew 11:25-30).

Introductory notes

General

Luke has a similar account of Jesus’ cry of gratitude in 10:21-22. In Luke it follows immediately after the announcement of woes to the unrepentant cities in Luke 10:13-16 – see also Matthew 11:20-24 – and the return of the seventy in 10:17-20.

“In the midst of a section (Matthew 11–13) largely devoted to the rejection of Jesus and his message, Matthew presents a group of sayings that highlight the revelation that Jesus brings and the kinds of people who accept it. The revelation concerns Jesus and his Father, and those who accept it are the ‘infants’ (nēpioi) rather than the professionally wise.” (Daniel J Harrington, The Gospel of Matthew, Liturgical Press, 2007, 168.)

The second part of our text – “Come to me etc.” – is unique to Matthew. Scholars conclude that the first part of the text comes from Q, the second from the tradition that Matthew alone draws on just as Luke has his own tradition apart from Q.

Specific

I thank you Father: Scholars have noted that there is a Hebrew equivalent to this phrase of acclamation in the Qumran Thanksgiving Psalms (Hodayot). “The prayer is a public proclamation of praise and thanks for what God has done.

Father, lord of heaven and earth: The address combines a title that implies Jesus’ special intimacy with God (“Father”) with the acknowledgment of this God as lord of both heaven and earth. It also prepares for the saying in which the special relationship between Father and Son is expressed.” (Daniel J Harrington, op cit, 166-167.)

the wise and the intelligent: Is this an ironic turn of phrase? Throughout all the Gospels there is much evidence of conflict between Jesus and the teachers of Israel. But, given the earlier reference to the lake-side towns, maybe the confrontation is broader than that. It does call to mind St Paul’s reference in his First Letter to the Corinthians: “I will destroy the wisdom of the wise, and the discernment of the discerning I will thwart” (1:19).

Infants: Probably a reference to his disciples – people of little or no learning and no social standing. Unlike the religious leaders.

no one knows the Son except the Father: This is more than metaphor. “‘Father’ and ‘Son’ are used absolutely here: ‘the Father’ and ‘the Son’ (see Matt 24:35; 28:19). It is not simply a parable about mutual knowledge between a father and a son (though such an analogy is at the root of the saying). The absolute use of Father and Son and the theme of mutual knowledge between them have affinities with the Johannine tradition, though there is no need to posit a direct literary relation between the two traditions here” (Daniel J Harrington, op cit, 167).

Come to me, all you that are weary and are carrying heavy burdens: The contrast between the learned/wise on the one hand with those who are unlearned/unwise – like the disciples but here including others listening – is maintained. Later Matthew is to speak of the scribes and the Pharisees who “bind heavy burdens” for people – see 23:4. Jesus offers a different way. A similar message – both Hebrew Scriptures and Christian Scriptures – is found in the metaphor of the shepherds, where the good shepherd is contrasted with the bad shepherd. See for example Matthew 9:35–10:6 and 15:24.

Reflection

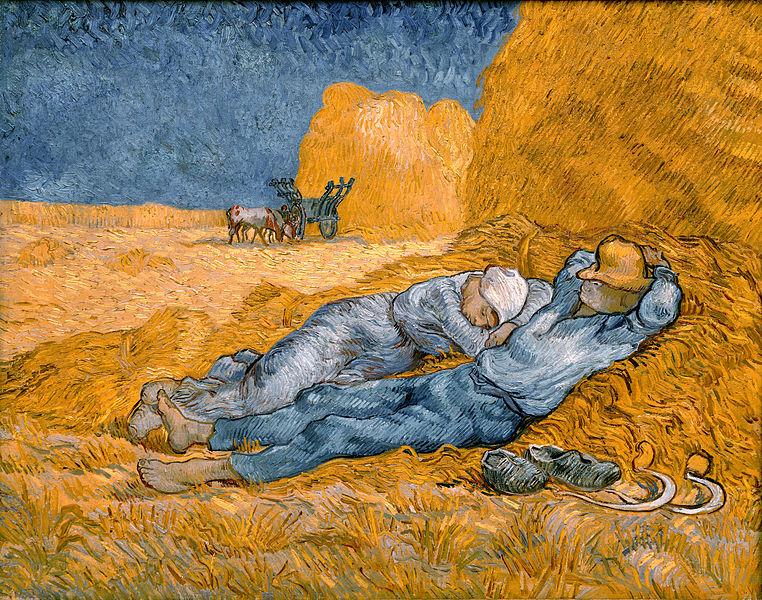

The image of an animal yoked to do work would have been familiar to everyone in the time of Jesus. The yoke provides discipline and direction, allowing the farmer and his animals to work as one. This was in fact a common enough image for teachers in Judaism. It was, for example, used in relation to the acquisition of wisdom and fidelity to the Torah. Thus, in Sirach (Ecclesiasticus) 51:26, the prospective student is urged to “put your neck under the yoke, and let your souls receive instruction.” It is an image of discipleship and freedom, not slavery and oppression as we might see it.

In today’s Gospel – Matthew 11:25-30 – Jesus applies the image to himself, clearly presenting it as an image of discipleship and liberation. We are reminded of Jesus’ response to Thomas, when he asked to know the way to the Father: “Jesus said to him, ‘I am the way ….’” (John 14:6).

Unfortunately, through the ages, the reality of discipleship and liberation has too often been usurped by that of slavery and oppression. What has been your experience? To what extent has fear been a significant motivator? To what extent have joy and freedom been part of your experience as a disciple of Jesus? Could you say you have been more drawn by delight than driven by duty?

St Thomas Aquinas writes of both delight (delectatio) and devotion (devotio) extensively in his works. Devotion is in fact a product of delight. Thus, Aquinas says that devotion is the act by which the will abandons itself light heartedly to God, to worship God and do as God wills (Summa theologiae, II-II, Q.82, a.1). This is in tune with St Augustine’s delectation victrix (“conquering delight”). As one Augustinian scholar writes: “This principle sets up the basic orientation of Augustinian theology and spirituality” (Fr John Melnick SSA, http://www.angelfire.com/pa5/augustinian16/ ) St Ignatius of Loyola placed great emphasis on the importance of “consolation” as distinct from “desolation”. This, according to Ignatius, requires “discernment”. Fr Jean Claude Colin – Founder of the Marist Fathers – is in this same tradition, when he says that Marists must help people to “taste God” and when they have “tasted God”, everything else will follow. Pope Francis, in his first Apostolic Exhortation, Evangelii Gaudium (“The Joy of the Gospel”) (2013), uses the word “joy” 109 times!

The question is not “law versus no law”. “Do not think that I have come to abolish the law or the prophets; I have come not to abolish but to fulfill” (Matthew 5:17). Jesus comes first and the rest follows. When you hear and accept Jesus’ invitation, “Come to me!” you will discover that he is “gentle and humble in heart, and you will find rest for your souls”. The “yoke” that he offers “is easy, and (his) burden is light”.

Remember Peter’s request in the storm on the lake: “Bid me come to you ….” (Matthew 14:28). Let that be your prayer. You will hear Jesus say repeatedly: “Come to me!”