Now when Jesus came into the district of Caesarea Philippi, he asked his disciples, “Who do people say that the Son of Man is?” And they said, “Some say John the Baptist, but others Elijah, and still others Jeremiah or one of the prophets.” He said to them, But who do you say that I am?” Simon Peter answered, “You are the Messiah, the Son of the living God.” And Jesus answered him, “Blessed are you, Simon son of Jonah! For flesh and blood has not revealed this to you, but my Father in heaven. And I tell you, you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church, and the gates of Hades will not prevail against it. I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven, and whatever you bind on earth will be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth will be loosed in heaven” (Matthew 16:13-20).

Introductory notes

General

Matthew and Luke – see 9:18-21 – depend on Mark 8:27-30 for this report.

Matthew makes some minor changes to Mark’s account – “Most of Matthew’s changes in his Markan source are minor editorial touches.” (Daniel J Harrington, The Gospel of Matthew, Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2007, 249.) For example he adds the Prophet Jeremiah to the popular guesses about Jesus’ identity.

Both Luke and Matthew keep Mark’s affirmation by Peter – “You are the Christ” – on behalf of the other disciples.

Matthew does however expand on the role of Peter: “The major change is the expansion of Peter’s confession in 16:16b–19. This material has no parallel in Mark or in any other Gospel source. By inserting it into his Markan source Matthew has altered the flow of the story. Whereas in Mark Peter’s confession is rejected or at least corrected, in Matthew it serves as the basis for Jesus’ blessing of Peter. The focus on Peter as the one who gets involved when problems emerge is typically Matthean (see Matt 15:15; 17:24–27; 18:21–22). In this text Peter is praised as the recipient of a divine revelation (16:17), called the foundation of the Church (16:18), and given special authority (16:19).” (Daniel J Harington, op cit, 249-250.) This expanded role affirmed in Peter also makes the following verses – in which Jesus rebukes Peter – particularly significant. Thus “the rock” finds a counterpoint in “the stumbling block” and the words from “my Father in heaven” find a counterpoint in “not God’s way but man’s”.

Specific

Caesarea-Philippi: A region north of Jerusalem, near the sources of the Jordan River.

the Son of Man: Neither Mark nor Luke use this expression. They move straight to the “say who I am”. The term, ‘Son of Man’, has currency beyond any references to Jesus: “(Son of Man) is a Semitic expression that typically individualizes a noun for humanity in general by prefacing it with ‘son of’, thus designating a specific human being, a single member of the human species. Its meaning can be as indefinite as ‘someone’ or ‘a certain person’. Used in Dan 7:13–14 to describe a cloud-borne humanlike figure, the expression—or at least the figure so designated in Daniel—became traditional in some forms of Jewish and early Christian speculation which anticipated a transcendent eschatological agent of divine judgment and deliverance. In the NT that agent is almost universally identified with the risen Jesus.” (G W E Nickelsburg, “Son of Man” in D. N. Freedman (Ed.), The Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary (Vol. 6), New York: Doubleday, 1992, 137.) Daniel Harrington notes: “Here Matthew uses ‘Son of Man’ as a way of talking about Jesus. It functions as a title connected with the many other instances of ‘Son of Man’ in the Gospel, not as a generic term or simply as a personal pronoun.” (Daniel J Harrington, op cit, 247.)

Messiah: The Greek word is Christos. The title has already been used on three occasions in Matthew – see 1:1 & 16-18 and 11:2. But this is the first time that one of the disciples uses the term of Jesus. Recall a similar naming of Jesus by the Canaanite woman in Matthew 15:22. One of the great ironies of the Gospels is that so many unlikely folk – and even demons – recognize Jesus as the Christ but those who should recognize him – namely the scholars and teachers – do not. The religious authorities either do not recognize the truth about Jesus or are unwilling to acknowledge it if they do.

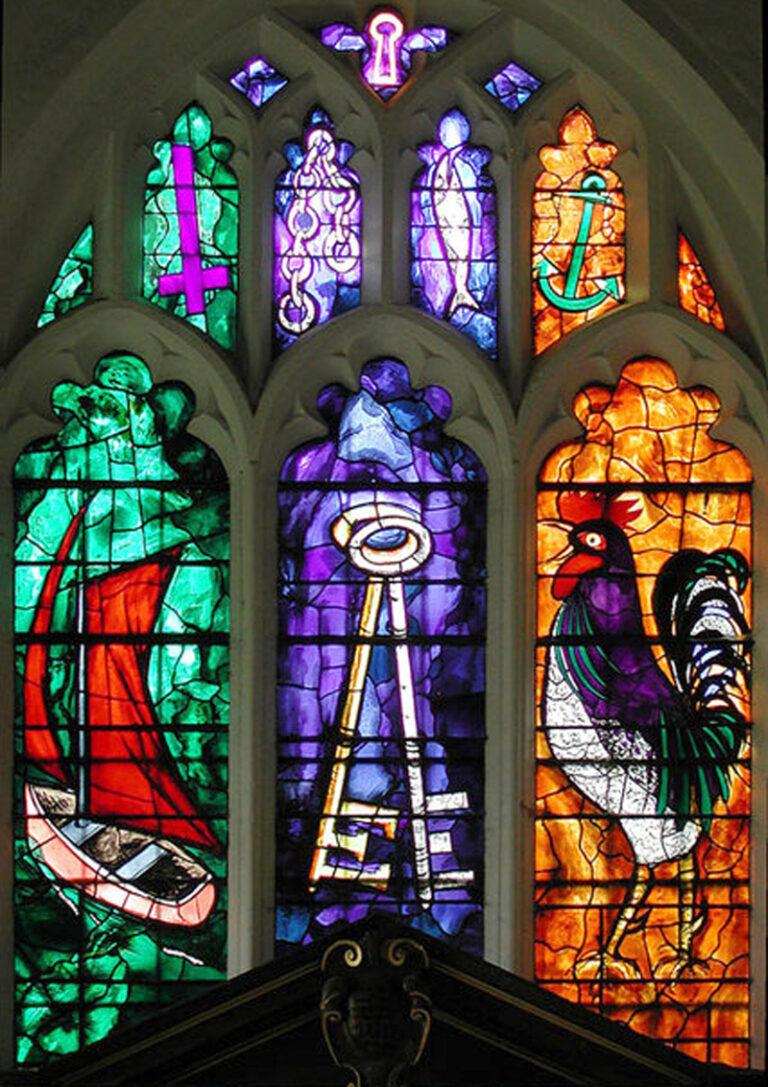

Simon son of Jonah: Scholars cannot agree on the origin of the naming of Simon Bar-Jonah as “Peter”. The naming is also found in John 1:42, Luke 6:14 and Mark 3:16. “Peter” is the English translation of the Greek Petros which is a pun on the word for “rock”, petra. It seems that this was not used as a name for a person before this.

church: The English word “church” here translates the Greek ekklēsia. It was a commonly used word at the time to designate a gathering of citizens called out from their homes into some public place, an assembly. We find such a usage in the account of St Paul’s dispute with the silversmith Demetrius in Ephesus – see Acts 19:23-41. In verses 32 and 39 there is a reference to the ekklēsia – that is the public gathering or assembly that was called to deal with the dispute. So, when Paul addresses the community in Corinth, urging them to maintain some decorum in their worship, he speaks of the times “when you come together as ekklēsia” (1 Corinthians 11:18). Paul seems to be adapting the word ekklēsia here, drawing on the common usage with which the Corinthians would have been very familiar, and pointing to the emergence of a new usage to match the new reason for gathering.

In the Old Testament, however, the Septuagint uses the word ekklēsia in a distinctively religious way to translate the Hebrew qāhāl Yahweh: “(In the Septuagint) the word describes an assembly convened for a religious act, often of worship (vg Dt 23; 1Kings 8; Psalm 22:26). It corresponds to the Hebrew qāhāl which is used especially by the Deuteronomic school to describe the assembly at Horeb (vg Dt 4:10), on the steppes of Moab (Deuteronomy 31:30), or in the promised land (vg Joshua 8:35 and Judges 20:2). It is also used by the Chronicler (vg 1 Chronicles 21:8 and Nehemiah 8:2) to describe the liturgical assembly of Israel during the time of the Kings or after the Exile. But if ekklēsia always translates qāhāl, this latter word is at times rendered by other words, particularly by synagoôgē (vg Numbers 16:3, 20:4 and Deuteronomy 5:22), which more often translates the sacerdotal word ēdāh. Church and synagogue are two almost synonymous terms (cf James 2:2); they will not be opposed in meaning until the Christians will appropriate the first for themselves and reserve the second for the obstinate Jews. The choice of ekklēsia by the Septuagint was doubtless influenced by the assonance qāhāl ekklēsia, but also by the etymological influences. Ekklēsia comes from ekkaleô (“I call from”, “I convoke”; of itself, it indicates that Israel, the people of God, was the assembly convoked by divine initiative. And it recalled a sacerdotal express in which the idea of call was expressed: klētē hagia, the literal translation of miqra qodes, “religious assembly” (Exodus 12:16, Leviticus 23:3 and Numbers 29:1).” (“Church” in Xavier Léon-Dufour SJ, editor, Dictionary of Biblical Theology, Geoffrey Chapman, 1972, 58-59.)

The Greek word ekklēsia is used on one other occasion in Matthew – see 18:17.

the gates of Hades: “Hades was a Greek god whose name means ‘the unseen one’. The Greek word was used to translate Hebrew terms for the underworld or Sheol. In Acts 2:27, 31 it refers to the abode of the dead; for the gates of Sheol see Isa 38:10. The idea in Matt 16:18 is that death and other powers opposed to God will not triumph over the Church (= assembly) of Jesus’ disciples.” (Daniel J Harrington, op cit, 248.)

In Acts 2:27 and 31, Peter is quoting Psalm 16:8-11(LXX). Joseph Fitzmyer writes: “What appears in v 27 is crucial. Psalm 16 is a lament, actually a psalm of personal trust in God; it expresses the psalmist’s faith in God’s power to deliver from evil and personal troubles, as he calls upon God to recall his constant seeking of refuge in divine help and makes renewed recognition of that help. As Peter makes use of it in his speech, it is applied to the risen Christ’s exaltation” (Joseph A Fitzmyer, The Acts of the Apostles: a new translation with introduction and commentary, New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 2008, 256). Fitzmyer continues, commenting specifically on v 27: “The important words are ‘the netherworld’ (hadēs), ‘your holy one’ (ton hosion sou), and ‘decay’ (diaphthora), which Peter applies from the Davidic psalm to the risen Christ, who is the preeminent ‘holy One’, whose status is not in the netherworld, and who has not experienced decay” (Ibid).

Reflection

The American scholar and essayist, Norman O Brown (1913-2002), wrote in his 1959 book, Life Against Death (New York: Random House): “Man aggressively builds immortal cultures and makes history in order to fight death” (101). What are we to think, say and do, about death? One way or another, these questions – and many others relating to death, confront us all. Death is inevitable. It demands a response. How – indeed, whether – we deliberately and explicitly respond to death, gives rise to many different behaviours and beliefs. Some of those are lifegiving. Some are death-dealing. The stakes are high.

Today’s Gospel – Matthew 16:13-20 – makes reference to Hades. “Hades was a Greek god whose name means ‘the unseen one’. The Greek word was used to translate Hebrew terms for the underworld or Sheol” (Daniel J Harrington SJ, The Gospel of Matthew, Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2007, 248). We get a good sense of what Hades or Sheol meant for the Jews, in the words of Isaiah 38:10-11: “I said: In the noontide of my days I must depart; I am consigned to the gates of Sheol for the rest of my years. I said, I shall not see the Lord in the land of the living; I shall look upon mortals no more among the inhabitants of the world”. In this view, death is not only inevitable, it is indomitable. Death has the final say.

Our text from Matthew gives us the Christian response: “The gates of Hades shall not prevail”. This is most obviously an expression of the belief that death and other powers opposed to God, will not triumph over the Church (ekklesia), the gathering of Jesus’ disciples. Less obviously, it is an expression of the belief that Jesus, in his dying, breaks through the gates of death and gives all those held by death the opportunity for freedom in him. Gates are an important part of the fortification and defense of a city. They are built to hold out against the enemy. No gates, no matter how strong, can hold out against the power of the Cross. “Death has been swallowed up in victory” (1 Corinthians 15:54 – see also Isaiah 25:8).

Death is not just the event that ends life. Throughout our days, living and dying are organically linked. Whether, in any moment, that link is life-giving or death-dealing for us, is largely a matter of our choice. For example, do we choose the dying involved in generosity or the death of greed, the dying involved in apologizing or the death of resentment, the dying involved in openness to the other or the death of prejudice, the dying involved in honesty or the death of dishonesty? We can become free through dying or entrapped by it.

Is it not a reasonable stance for the Christian, to be a hope-filled pessimist? Our hope is grounded in Jesus Christ and our capacity as free agents to live the dying that our days demand of us through him, with him and in him. Our pessimism is warranted in the face of the pervasive denial of death in our culture – a denial that can seduce any of us any time.

A video presentation of the Reflection may be found on YouTube via https://stpatschurchhill.org/