Gospel Notes by Michael Whelan SM

“I am the good shepherd. The good shepherd lays down his life for the sheep. The hired hand, who is not the shepherd and does not own the sheep, sees the wolf coming and leaves the sheep and runs away—and the wolf snatches them and scatters them. The hired hand runs away because a hired hand does not care for the sheep. I am the good shepherd. I know my own and my own know me, just as the Father knows me and I know the Father. And I lay down my life for the sheep. I have other sheep that do not belong to this fold. I must bring them also, and they will listen to my voice. So there will be one flock, one shepherd. For this reason the Father loves me, because I lay down my life in order to take it up again. No one takes it from me, but I lay it down of my own accord. I have power to lay it down, and I have power to take it up again. I have received this command from my Father” (John 10:11-18 – NRSV).

Introductory notes

GeneralThis text comes immediately after the statement by Jesus: “I have come so that they may have life and have it to the full” (10:10). This statement names a truth that is at the very heart of the Incarnation: God seeks us out that we might live to our potential as creatures made in the image and likeness of the One who is the Source of all that is Good and True, Beautiful and Unifying! This has given rise to a theological theme more pronounced in Eastern Christianity than Western Christianity – the theme of Theosis or “Divinization”. Thus, St Gregory of Nazianzen writes in the 4th century: “The human being is an animal who has received the vocation to become God”. (St Gregory of Nazianzen, spoke these words when he gave the eulogy at the funeral of his friend, St Basil of Caesarea, in 379. He was actually quoting St Basil himself.)

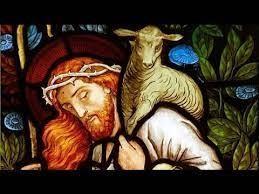

John uses a well-known metaphor – the shepherd – to indicate Jesus’ place in God’s plan.

Specific

good: The Greek word is kalos. William Barclay calls this “the word of winsomeness”: “We may best of all see the meaning of kalos, if we contrast it with agathos which is the common Greek word for ‘good’. Agathos is that which is practically and morally good; kalos is not only that which is practically and morally good, but that which is also aesthetically good, which is lovely and pleasing to the eye. …. When a thing or person is agathos, it or he is good in the moral and practical sense of the term, and in the result of its or his activity; but kalos adds to the idea of goodness the idea of beauty, of loveliness, of graciousness, of winsomeness. Agathos appeals to the moral sense; but kalos appeals also to the eye.” (William Barclay, “KALOS: The Word of Winsomeness”, in W. Barclay, New Testament Words, SCM Press, 1980, 154.)

Barclay sums up: “The shepherd does not look after his sheep with only a cold efficiency. He looks after them with a sacrificial love. When the sheep are in trouble, he does not nicely calculate the risk of helping them; he gives his life for the sheep. He does not give so many hours’ service to the sheep per day, and carefully calculate that he must work so many hours a week. All through the day he watches over them, and all through the night he lies across the opening in the sheep-fold so that he is literally the door. Here we have the same idea again. The good shepherd is the shepherd whose service is a lovely and a heroic thing because it is a service, not rendered for pay, but rendered for love. The basic idea in the word kalos is the idea of winsome beauty; and we are bound to see that nothing can be kalos unless it be the product of love. Deeds which are kalos are the outcome of a heart in which love reigns supreme. The outward beauty of the deed springs from the inward magnitude of the love within the heart. There is no English word which fully translates kalos; there is no word which gathers up within itself the beauty, the winsomeness, the attractiveness, the generosity, the usefulness, which are all included in this word” (William Barclay, William, op cit, 159).

Raymond Brown complements Barclay when he says the word kalos could be translated here as “noble”. He writes: “(P)erhaps ‘noble’ would be more exact here and ‘model’ more exact in vs. 14. Greek kalos means ‘beautiful’ in the sense of an ideal or model of perfection; we saw it used in the ‘choice wine’ of 2:10. Philo (De Agric, #6, 10) speaks of a good (agathos) shepherd. There is no absolute distinction between kalos and agathos, but we do think that ‘noble’ or ‘model’ is a more precise translation than ‘good’ for John’s phrase. In the Midrash Rabbah ii 2 on Exod 3:1, David who was the great shepherd of the OT is described as yāfeh rōʿeh, literally ‘the handsome shepherd’ (see 1 Sam 16:12)” (R E Brown, The Gospel according to John (I–XII): Introduction, translation, and notes (Vol. 29), New Haven; London: Yale University, 2008, 386).

shepherd: The metaphor of the shepherd is a rich one in the Israelite tradition: “The traditions of Israel’s life in the desert seem to have given rise to the thought of God as their shepherd, for it is during the early period that he alone is viewed as shepherd and protector (Gen 48:15; 49:24; cf. Deut 26:5–8; Jer 13:17; Mic 7:14). Though God is seldom called a shepherd, the concept was common and remained a favorite idiom throughout Israelite history (cf. Pss 31:4—Eng v 3; 80:2—Eng v 1). God is pictured carrying in his bosom animals which cannot keep up, and mindful of the sheep which have young, he does not overdrive them (Isa 40:11; cf. Gen 33:13; Ps 28:9).

“The symbol was a favorite for depicting the Exodus. In one of Israel’s earliest traditions, the Song of Moses, the image of God as a shepherd leading the people to safe pastures is implied (Exod 15:13, 17), and later reflection upon this event shows God as a powerful leader driving out other nations and making room for his own flock (Ps 78:52–55, 70–72). A number of passages use the figure to compare the return from Babylonian exile with the Exodus (Jer 23:1–8; 31:8–14; Isa 40:11; 49:9–13). God’s loyalty and devotion to an individual sheep is presented in the classic Shepherd Psalm (23); it is possible, however, that this psalm alludes to the exiled community and is a symbolic expression of their return to Palestine (cf. Isa 49:9–13 and Psalm 121).” (J W Vancil, “Sheep, Shepherd”. In D. N. Freedman (Ed.), The Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary (Vol. 5), New York: Doubleday, 1992, 1189.)

The hired hand, who is not the shepherd and does not own the sheep: The metaphor of “ownership” is a profane image. But it achieves its purpose here. The one who is a “hired hand” will normally not have the same kind of commitment to the sheep as the one who “owns” them and whose livelihood – and whose family’s livelihood – depends on their well-being. The metaphor evokes a gut reaction – “Yes, that’s right!”. The listeners are then better prepared to hear the deep truth that follows: Jesus is like one whose whole existence depends on the well-being of his disciples!

I know my own and my own know me: For the Western mindset, so dominated by rationalism, this statement is difficult to comprehend in the way Jesus would have intended it. The Jewish philosopher, Abraham Joshua Heschel, sums it up: “Geographically and historically Jerusalem and Athens …. are not too far removed from each other. Spiritually they are worlds apart.” (Abraham Joshua Heschel, God in Search of Man: A Philosophy of Judaism, Straus & Girouox, 1978, 15.) The Western mindset is shaped by rationalism and abstraction. The Semitic mindset – more characteristic of Jesus – is much more experiential and concrete. “I know mine and mine know me” speaks of a lived and living relationship.

I lay down my life: In this brief text there are five references to Jesus “laying down his life”. This expression embodies a revelation that runs like a golden thread throughout John’s Gospel. Ultimately it is summed up in words such as doxa (“glory”) and doxazo (“glorify”). In the conversation with Nicodemus – Chapter 3 – Jesus declares: “so must the Son of Man be lifted up” (3:13). The “laying down” and the “lifting up” are of a piece. The glory of God is manifest in this. This is the ultimate revelation of God who “so loved the world he gave his only Son” (3;16). The concept of glory is introduced right at the beginning of John’s Gospel: “(T)he Word became flesh and lived among us, and we have seen his glory” (1:14). As the Gospel unfolds, so the centrality of God’s glory being revealed in and through Jesus becomes clearer: “(W)hat should I say—‘Father, save me from this hour’? No, it is for this reason that I have come to this hour. Father, glorify your name” (12:27-28). The footnote in the Jerusalem Bible to John 17:1 – where there is a reiteration of 12:27-28 – observes: “The glory of Son and Father are one, cf 12:28; 13:31”. Finally, Jesus declares on the Cross: “He said, ‘It is finished’” (19:30). The Greek verb, teleō, means “finish”, “complete” or “accomplish”. The mission of the Son in revealing the Father’s love has been accomplished.

Reflection

“Get a life!” is a somewhat flippant statement that has gained currency in our days. It may have a useful meaning in the given context, but it is probably not intended as a summons to a profound reflection. Whilst there is no “answer” to the question, “What is life?”, there is some value in listening and wondering about it. Today’s Gospel – John 10:11-18 – invites such a response.

John’s Gospel refers explicitly to “life” more than fifty times – sometimes in the ordinary sense of that word, but mostly in an other than ordinary sense. The ordinary Greek word, zoē, is used in both cases. So, when we are reading John’s Gospel, we need to be alert to the two senses. When the word is used in the second sense – the other than ordinary sense – we are invited to pay particularly close attention and listen at depth.

The second sense of the word is used in one of the opening statements of John’s Gospel: “What has come into being in him was life, and the life was the light of all people” (1:1-4). And again, in Chapter 3, in the conversation with Nicodemus, we hear Jesus say, “God so loved the world that he gave his only Son, so that everyone who believes in him may not perish but may have eternal life” (3:16). This expression – “eternal life” (aiōnion zoe) – is found a number of times in John’s Gospel – see for example 3:36, 4:14 & 36, 5:24 & 39, 6:25, 40, 47, 54 & 68, 10:28 and 12:25.

Three times in today’s Gospel we hear Jesus say he “lays down his life”. Most significantly, the third time he says: “I lay down my life in order to take it up again”. I suggest that both senses of the word are operative here – life in the flesh and “eternal life”. Significantly enough, these references occur immediately after a memorable statement in which the second sense is clearly implied: “I have come so that they may have life and have it to the full” (10:10). In fact, the two senses are interdependent. “The Word became flesh and lived among us” (1:14). We come to “life” – in the other than ordinary sense – through his being in the flesh. He is “the Way, the Truth and the Life” (14:6).

Yes, there is something automatic about life in the first sense of the word. Given reasonable health and nutrition, you will have a life. However, this life may or may not become a life of moral integrity. Such a life is available to those with the knowledge and discipline and courage and commitment to apply themselves. Beyond that life of moral integrity, however, there is the “life” that is pure gift. That “life” cannot be achieved by merely human means. Yet it is the very flowering and fulfilment of ordinary life. It is what we are made for. This “life” – this flowering and fulfilment of our humanity – is on offer in Jesus. It is concisely summed up by him: “Abide in me as I abide in you” (15:4). This is the “life” we all long for, whether we realise it or not.

Is it possible to miss your life – in whole or part – even as you walk around among your peers, successful, held in esteem, comfortable and secure? What is life, really?